For the first half-century of the Space Age, the cosmos was the exclusive domain of the nation-state. When Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth and Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon, they did so as emissaries of superpowers, their triumphs echoing as geopolitical statements. The entities that launched them—NASA, Roscosmos (then the Soviet space program), and later the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)—were colossal, publicly funded instruments of national prestige, scientific discovery, and military strategy. This era of the “public space monolith” was not an accident of history but a necessity. Today, however, the skyline is crowded with new logos: SpaceX’s stylized ‘X’, Blue Origin’s feather, and Rocket Lab’s electron orbital. The rise of these private entities signals a profound transformation. This article explores why public agencies once held a monopoly, the factors that catalyzed the private revolution, and what the future holds for the intertwined destinies of public and private spacefarers.

The Age of the Public Monolith: Why Governments Led the Charge

In the beginning, space was simply too hard, too expensive, and too strategically vital to be left to anyone but governments.

The Colossal Cost and Risk: Developing rocket technology from scratch required investments measured in percentages of a nation’s GDP. The Apollo program, at its peak, consumed over 4% of the U.S. federal budget. Failure was not just a business loss but a national embarrassment. Only governments could bear such financial and political risk.

Geopolitical and Military Imperative: The space race was a direct extension of Cold War ballistic missile development. Satellite technology meant reconnaissance, communication, and navigation supremacy. This was a domain of national security, inherently governmental.

Absence of a Commercial Market: In the 1960s and 70s, there was no obvious, profitable customer for routine space access. Telecommunications satellites were nascent, and the concept of a private space industry was science fiction. The “customer” was the state itself, for science and security payloads.

The “Mega-Project” Model: Agencies like NASA and ISRO excelled at the “mega-project”: singular, monumental goals with almost unlimited (though politically volatile) budgets. This model achieved the impossible—the Moon landings, Viking Mars missions, and formidable launch vehicles like the Space Shuttle and Ariane rockets, operated by the publicly-backed consortium Arianespace.

These agencies performed miracles, but the model had inherent limitations: bureaucracy, cost-plus contracting that discouraged efficiency, and programmatic instability tied to political winds. The Space Shuttle, for all its brilliance, was staggeringly expensive and risky. By the 1990s, a convergence of factors created an opening for change.

The Catalysts of the Private Dawn: A Perfect Storm

The shift from a government-only club to a public-private ecosystem was triggered by several key developments:

Government Becomes an “Anchor Tenant”: A pivotal moment was the U.S. government’s decision to retire the Space Shuttle and seek private solutions for cargo and crew transport to the International Space Station (ISS). NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) and Commercial Crew programs did not prescribe how to build the spacecraft. Instead, they set goals and paid for milestones, unleashing private innovation. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Dragon capsule are direct results. The state transitioned from being the sole operator to being a foundational customer, creating the initial market.

Technology Democratization: Advances in computing, materials science, and manufacturing (like 3D printing) drastically reduced the barrier to entry. Startups like Rocket Lab could use carbon composite fabrication and automated systems to build small launch vehicles in ways impossible in the Apollo era. The “secret sauce” of rocketry became more accessible.

The Visionary Capitalist: The influx of private capital from billionaires with long-term visions—Elon Musk (SpaceX), Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), and others—was crucial. They were willing to absorb massive losses for years, investing not for quarterly returns but for transformational goals like Mars colonization or millions living and working in space. Venture capital followed, funding a new generation of startups.

The Explosion of the Commercial Satellite Market: The demand for broadband internet (Starlink, OneWeb), Earth observation (Planet Labs), and small satellites created a booming market. The slow, expensive, and infrequent launch schedules of traditional government rockets could not serve this need. Agility and frequency became paramount, a niche private companies filled perfectly.

Cultural Shift: “Move Fast and Break Things”: Private companies, free from the intense public scrutiny and risk-aversion of government agencies, embraced iterative, agile development. SpaceX’s famous “fail fast, learn faster” approach with prototype rockets would be politically untenable for NASA. This culture of rapid innovation drove down costs and accelerated progress at a blistering pace.

The Future: A Symbiotic Orbit, Not a Collision Course

Looking ahead, the narrative is not of replacement, but of increasingly sophisticated symbiosis. We are moving toward a clear, though overlapping, division of labor:

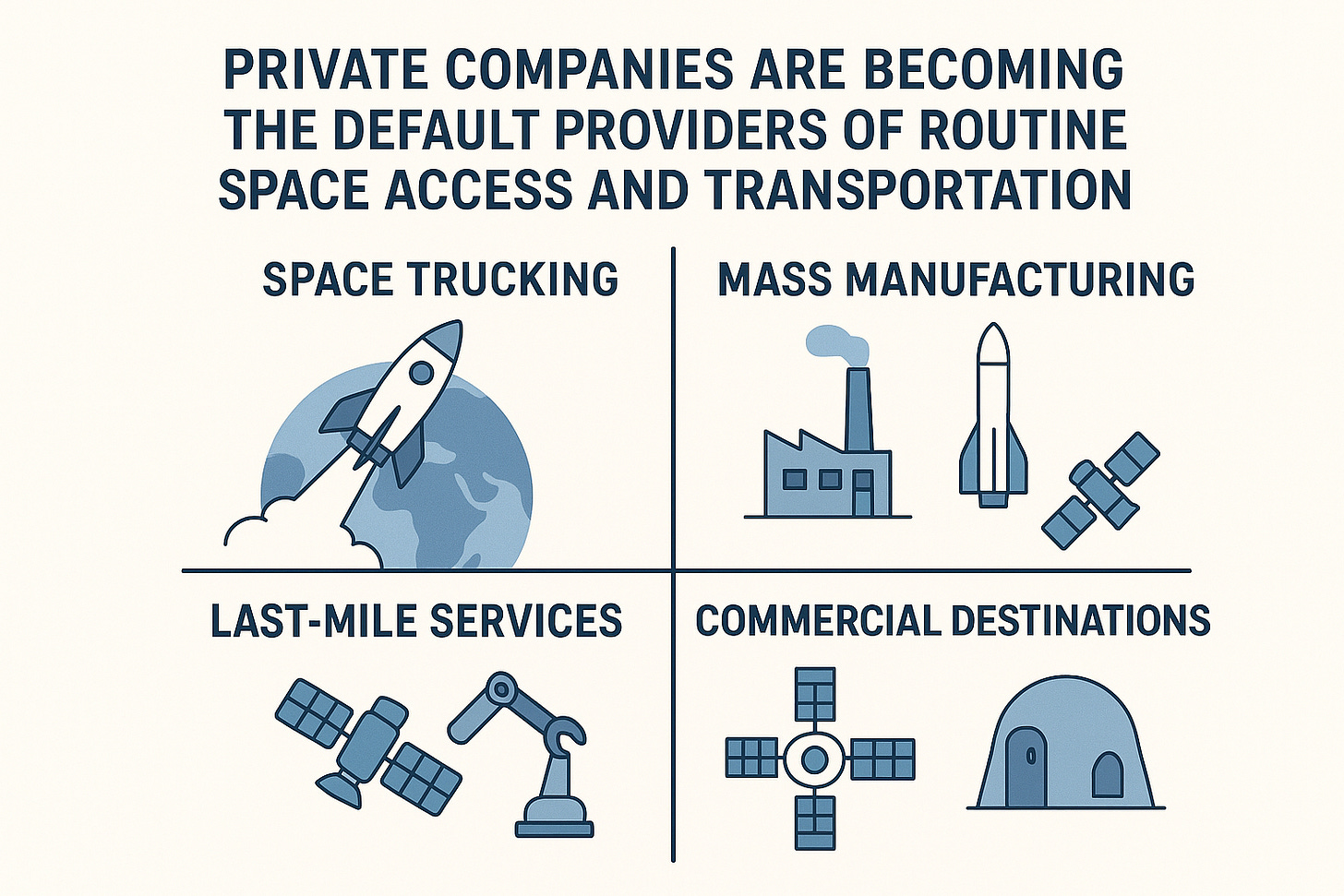

The New Private Role: The Logistics and Infrastructure Backbone

Private companies are becoming the default providers of routine space access and transportation. This includes:

Space Trucking: Ferrying cargo and crews to LEO (Low Earth Orbit) and the Moon.

Mass Manufacturing: Building standardized, low-cost satellite buses and rockets (SpaceX’s Starlink factory model).

Last-Mile Services: On-orbit satellite servicing, refueling, and debris removal (companies like Astroscale).

Commercial Destinations: Building and operating private space stations (Axiom Space) and lunar habitats.

The Evolving Public Role: The Pathfinder and the Regulator

Public agencies will increasingly shed their operational trucking roles and refocus on missions only they can do:

Deep Space Exploration: Robotic and crewed missions to Mars, the asteroids, and beyond. These are high-risk, high-science, zero-profit endeavors that define our species’ reach.

Fundamental Science & Research: Orbiting observatories like Hubble and JWST, and deep-space probes. These expand human knowledge without a direct commercial ROI.

Regulation, Stewardship, and Safety: As LEO becomes congested, governments must establish the “rules of the road,” license activities, and ensure sustainable use of orbits. They remain the ultimate guardians of planetary protection.

“Market Maker” for Ambitious Goals: By setting audacious goals (e.g., NASA’s Artemis lunar base), governments create the initial demand that spurs private investment and innovation for entirely new markets, like lunar ice mining.

Should Public Space Agencies Still Exist? An Unequivocal Yes.

The argument to dismantle public agencies in favor of private ones is flawed. The private sector optimizes for efficiency, profit, and market demand. It is ill-suited for the pure science of a Voyager probe, the decades-long investment in a Mars sample return, or the stewardship of celestial environments. Public agencies operate on behalf of all humanity, driven by curiosity, exploration, and long-term strategic interest.

The future is not a binary choice but a powerful partnership. NASA no longer builds rockets to LEO; it buys seats from SpaceX. ESA invests in startups like Rocket Factory Augsburg for sovereign launch capacity. ISRO launches commercial satellites to fund its ambitious science missions.

This synergy creates a virtuous cycle: public agencies set visionary goals and provide initial funding, private companies drive down costs and increase capability through competition, which in turn enables even more ambitious public and private ventures. We are transitioning from a model where government did everything, to one where it catalyses and purchases services, freeing itself to push the boundaries of the unknown further and faster than ever before.

The cosmos is vast enough for both. The public agency will remain our guiding compass, pointing to the next horizon. The private company will build the ships, the roads, and the cities that get us there. Together, they are opening the final frontier not just to a handful of astronauts, but to all of civilization.

Excellent historical fram

ing of the institutional shift from state monopoly to public-private partnership. Your observation that the transition wasn't ideological but pragmatic is key, government agencies didn't fail so much as succeed in creating conditions for private sector entry by proving feasibility and building infrastructure. The "anchor tenant" model is particulary clever policy design, it provides guaranteed revenue while forcing agencies to think like customers rather than operators. One thing you could explore further is how this model performs under geopolitcal stress, if US-China space competition intensifies, we might see a partial reversal back toward state dominance.