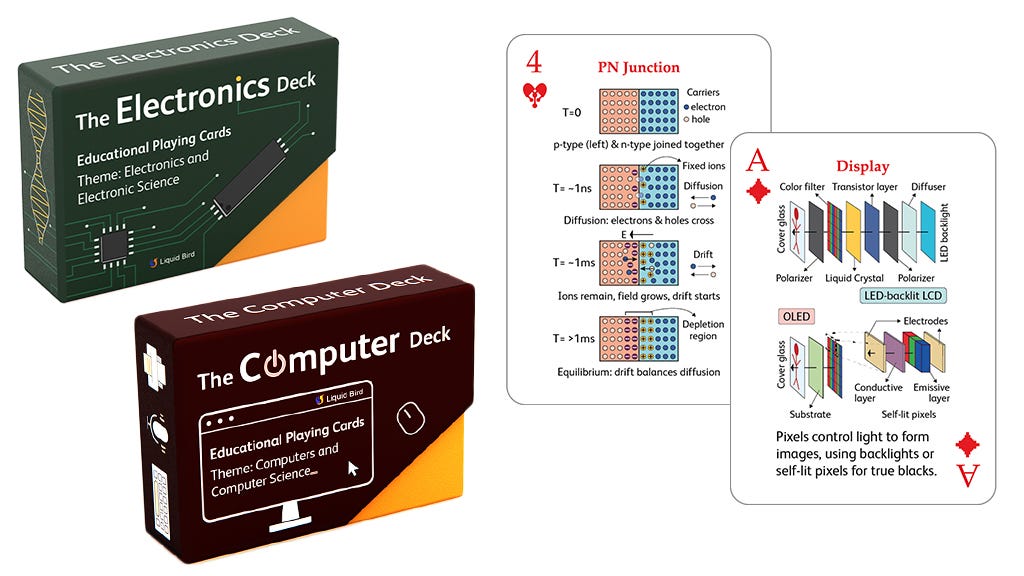

A few weeks ago, we launched two educational decks of playing cards on Electronics and Computers. If you are curious to get a good overview of these fields in a fun and organized manner, do check the project here on Kickstarter.

Introduction

Think of the International Space Station as the big school where astronauts from many countries learned how to live and work in space for more than two decades. The ISS taught us how to grow protein crystals, study Earth, test new tech, and even figure out how to keep humans healthy far from home. But every school has an age, and the ISS is getting old. Let us walk through when and why it will step down, then meet the other stations that want to share the sky with us next.

ISS retirement: when and why

NASA and its partners plan to operate the ISS through 2030. After that, the plan is to retire the complex because of age, rising maintenance risks, and the growing role of commercial stations and national programs that can take over science and crew transport. The station has been priceless as a continuous human outpost since the year 2000, hosting thousands of experiments, building international cooperation, and proving long-duration human spaceflight is possible and useful.

A quick note on China’s Tiangong

China built its own modular station called Tiangong, finished assembly in the early 2020s, and now operates it on a steady cadence of crewed and cargo flights. Tiangong is smaller than the ISS but modern, purpose-built, and already serving as China’s primary lab for long-duration astronaut stays and experiments. China is also adding advanced tech, such as on-orbit AI assistants and planning Xuntian, a big telescope that will rendezvous with the station’s orbit.

The new players — six stations you should know

Below are the major planned or proposed stations that could carry the torch after the ISS.

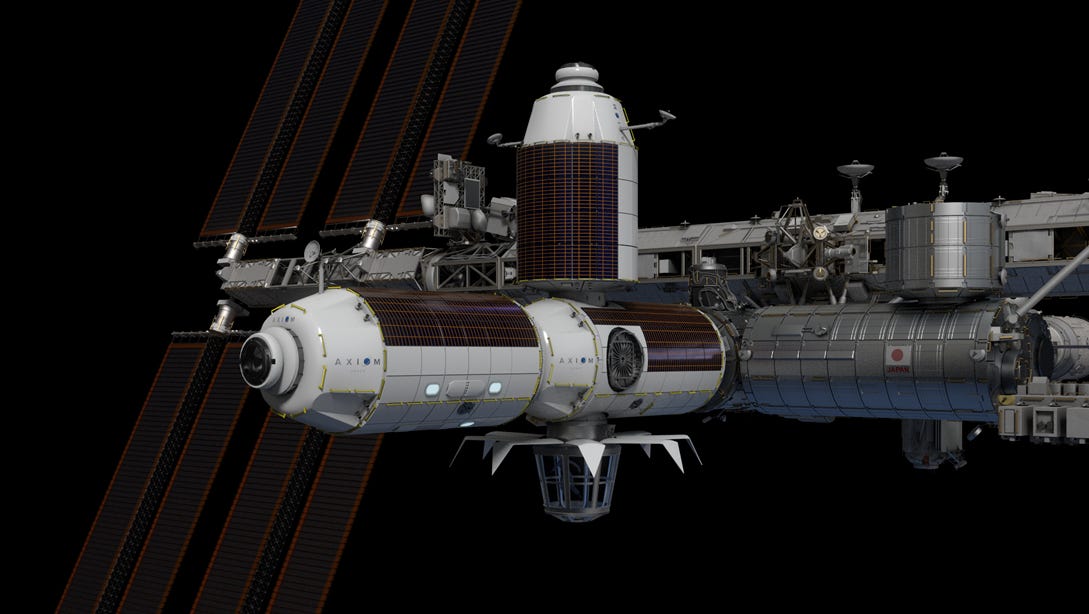

Axiom Station (Axiom Space)

Axiom plans to build the first commercial modules that will physically attach to the ISS, be tested while the ISS is still operating, and then separate to become an independent commercial station. The idea is incremental: start as an add-on, then spin off into a free-flying facility that supports research, industry, and private astronauts.

Why it matters: Axiom’s path is practical. By taking modules aboard the ISS first, they reduce risk and prove systems in orbit. When Axiom separates, it will already have flight-proven life support, crew quarters, and lab space. This model lowers the barrier for companies and governments that want reliable LEO services without building an entire station from scratch.

Who and timing: Axiom Space, a U.S. company, leads this effort with international partners. The modules and roadmap target the late 2020s for the transition from attached modules to an independent outpost.

Haven-1 (Vast)

Haven-1 is a single-module commercial habitat designed primarily for private astronauts, research, and demonstration missions. It is built to be launched and operated by a private company as a stand-alone mini-station with internal space for a small crew, science, and even media or creative projects.

What makes it different: Haven-1 aims to be lightweight and focused. Instead of a sprawling complex, it is a compact, purpose-built station meant to support commercial operations: short stays, quick experiments, and private missions. If it reaches orbit on schedule, it will help show how small, nimble stations can serve a market beyond big national programs.

Who and timing: Vast is the developer. Public estimates and reporting around 2025–2026 pointed to launch targets in the mid-2020s, but commercial timelines are fluid and depend on rockets and certification. Recent reporting suggests final build and launch preparations are underway for a mid-decade flight.

Orbital Reef (Blue Origin + Sierra Space and partners)

Orbital Reef was designed as a “mixed-use business park” in low Earth orbit. The concept includes habitats for research, manufacturing, tourism, and logistics. The plan blends rigid modules and inflatable elements to create flexible space for many customers.

What makes it different: Orbital Reef’s pitch is a commercial campus where companies lease racks, operate labs, and host paying visitors. The approach is to make LEO more like a business district where many tenants run their own projects rather than a single government lab.

Who and timing: Led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space with multiple industrial partners, Orbital Reef received early NASA support and attention. Progress has been steady but quieter publicly than some other projects, and timelines remain less certain than the NASA-funded winners like Starlab or Axiom. That uncertainty partly stems from the technical and business complexity of building a multi-use station.

Bharatiya Antariksh Station (India’s proposed station)

India’s Bharatiya Antariksh Station (BAS) is a national modular station planned by ISRO. It will be much smaller than the ISS but built to support Indian human spaceflight goals, science experiments, and technology demonstrations in orbit. Public ISRO releases describe a multi-module configuration with robotics, life support and docking systems that are largely indigenous.

What makes it different: BAS is a nation-state project focused on building local capability. It will test India’s life support systems, docking technology, and human-tended operations. For India, BAS is a strategic step: it leverages experience from Gaganyaan (India’s crewed program) and demonstrates independent long-duration human spaceflight capability.

Who and timing: ISRO leads BAS. Public plans have suggested module launches beginning in the late 2020s, with the program stretching into the 2030s for completion. Timelines have shifted as Gaganyaan and related tests advance, but the program is active with prototypes and module designs in development.

Starlab (Voyager/Nanoracks + Airbus and partners)

Starlab is a compact, commercial research station developed by Voyager Technologies in partnership with Airbus and other industrial players. Its design focuses on life sciences, pharmaceuticals, and industrial research, aiming to provide high-throughput microgravity experiments for commercial and government customers.

What makes it different: Starlab emphasizes a high-power service module, a dedicated lab/habitat module, and a science park ecosystem. It was designed to be launched largely in one piece and operate as a dependable, research-focused platform. NASA has funded parts of early development under its commercial LEO initiatives.

Who and timing: Voyager Space together with Airbus and other partners leads the project. Public reporting around 2024–2025 placed Starlab’s target launch window near 2028, with development milestones and design reviews moving into full-scale production. The plan uses heavy-lift launch capability such as Starship to put large modules into orbit in fewer launches.

Russian Orbital Service Station (ROS)

ROS is Russia’s proposed follow-on to its segment of the ISS. The new Russian Orbital Service Station is intended to be a sovereign Russian complex that can host crew, research, and commercial activity separate from the international ISS partnership. It represents Russia’s long-term plan to continue independent human presence in LEO.

What makes it different: ROS is conceived as a national station with Russian modules, systems, and a focus on autonomy from the previous international ISS arrangement. It may reuse some hardware lessons learned from the Russian Orbital Segment but is designed as a new build with newer systems.

Who and timing: Roscosmos is the lead organization. Early public documents suggested construction beginning in the mid-late 2020s, with phased module launches to assemble the station. As with many large space projects, precise timing depends on budgets, industrial capacity, and policy choices.

How these stations fit together

Consider the post-ISS era as a move from one big, shared school to a neighborhood with many kinds of buildings. Some are national schools like China’s Tiangong and India’s BAS. Some are private labs like Axiom, Haven-1, and Starlab. Others are hybrid business parks like Orbital Reef. The practical outcome is more options for research, manufacturing, tourism, and national presence in LEO. NASA and other agencies plan to rely more on commercial destinations for low Earth orbit work while focusing their own resources on lunar exploration and deep space.

Outstanding comprehensive survey of the post-ISS landscape. Your framing as a transition from "one big shared school to a neighborhood with many buildings" elegantly captures the fundamental shift in LEO architecture. The detail on Axiom's incremental approach - testing modules while attached to ISS before separation - is particularly strategic and underappreciated as a risk-mitigation model. I appreciate how you've contextualized each station's distinct value proposition rather than treating them as direct competitors: Axiom for proven commercial operations, Haven-1 for nimble private missions, Orbital Reef for multi-tenant industrial capacity, BAS and ROS for sovereign strategic capability, and Starlab for high-throughput research. The Starlab section's emphasis on using heavy-lift capability (Starship) for fewer launches is a critical point - launch vehicle evolution is enabling new station architectures that weren't feasible in the ISS era. The inclusion of India's BAS is important; too many Western analyses overlook ISRO's rapid progress toward indigenous crewed capability. Your assessment of NASA shifting focus to lunar/deep space while leveraging commercial LEO destinatons captures the policy logic driving this entire transition. Excellent educational piece!