Meet the N1 Rocket – The Soviet Giant That Never Flew

Did Russia Ever Try to Land on the Moon?

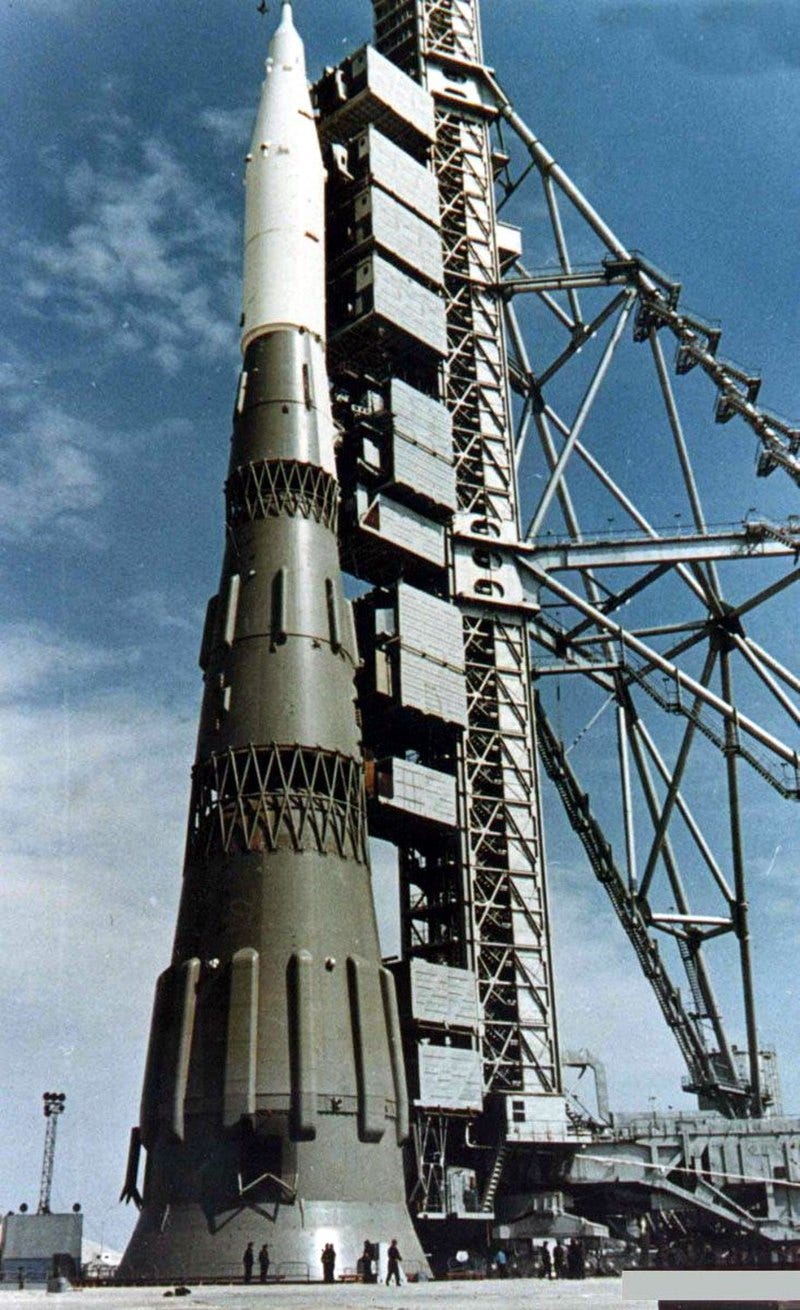

If you think only America aimed for the Moon, think again. The Soviet Union didn’t just dream about it—they built a rocket that could’ve taken them there. It was called the N1, a monster rocket as tall as a 35-story building, packed with 30 engines, and designed to send cosmonauts to the lunar surface.

In theory, it could’ve matched NASA’s mighty Saturn V. But in reality? It never flew successfully. Not even once.

So yes, Russia did try to land on the Moon. But their best shot, the N1, ended up as one of the biggest ‘what-ifs’ in space history.

The Race to the Moon

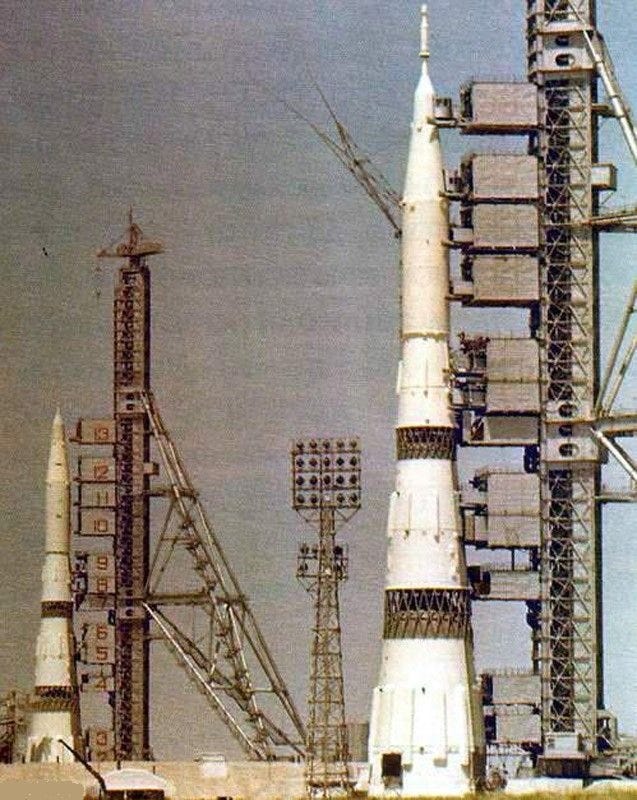

In the 1960s, space was the main stage for the Cold War. After Sputnik and Gagarin’s success, the Soviet Union had a head start. But once President Kennedy announced America’s Moon goal, the race was officially on. The U.S. put everything behind Apollo. The USSR, always secretive, quietly began work on their own Moon mission. The heart of that effort was the N1 rocket, designed by the legendary engineer Sergei Korolev, also known as the Chief Designer.

Korolev wanted a rocket that could do it all—deliver a crew to lunar orbit, land a cosmonaut on the Moon, and bring him back safely. That rocket was the N1. It had three stages and could lift nearly 95 tons into low Earth orbit. It used kerosene and liquid oxygen as fuel, which was common, but what made it unique (and risky) was its engine layout: 30 engines in the first stage, the Block A.

Why 30 Engines?

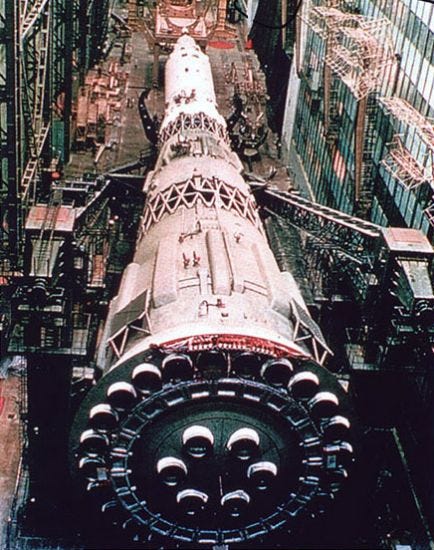

The U.S. Saturn V used five huge F-1 engines in its first stage. The Soviets couldn’t match that power in a single engine, so they chose to cluster smaller ones. The result? A ring of 24 NK-15 engines and six more in the center. That meant complex plumbing, heavy vibration, and a coordination nightmare. Managing 30 engines without modern computers was like trying to juggle bowling balls on a unicycle. The idea was brilliant on paper but incredibly fragile in the real world.

And then Korolev died in 1966 during a routine surgery. His absence left a vacuum in leadership, and the project started to unravel. Now let’s walk through the four launches and how each one shaped the downfall of the N1.

1. February 21, 1969 – First Launch (N1-3L)

The first real test of the N1 happened just months before Apollo 11’s Moon landing. There was no crew on board—this was just to test the rocket itself. The engines ignited, and for a moment, it looked like it would work. But 66 seconds into flight, things went south.

One of the engines caught fire due to a fuel line issue, and the onboard control system shut down all engines. The rocket crashed in the Kazakh desert, well short of space. The main cause? Vibration, poor quality control, and rushed testing. The fix? Engineers tried to redesign the control system and added vibration dampers for the next flight.

2. July 3, 1969 – Second Launch (N1-5L)

This one was a disaster of historic scale. Just 16 days before Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, the Soviets made their second attempt. At liftoff, a small piece of debris—a loose bolt—got sucked into the oxidizer pump of one engine. The pump exploded, starting a fire. One second into the flight, the control system panicked and shut off all engines.

The N1 fell back onto the pad and exploded in a blast so huge it flattened everything around it. The explosion released energy close to that of a small nuclear bomb. It destroyed the launch complex completely. Luckily, no one was hurt, but the entire Soviet Moon program was pushed back by years. After this, they rebuilt the launchpad from scratch and focused heavily on improving engine insulation and cleanliness during assembly.

3. June 27, 1971 – Third Launch (N1-6L)

This version had upgraded engines and slightly redesigned systems. There was hope again, especially since it came a few months after the Apollo 14 mission. The rocket did better—it actually made it to 50 kilometers altitude. But then the control system detected an engine imbalance and shut down a few motors. The rocket lost stability, started spinning, and had to be destroyed by ground command.

The main issue? The same control system weakness and engine management problems. More lessons were learned. The next variant would use new NK-33 engines with better thrust and reliability. But it was starting to become clear: without Korolev’s leadership and coordination, fixing one problem just revealed three more.

4. November 23, 1972 – Fourth Launch (N1-7L)

This was the final shot. The rocket had the improved engines, new plumbing, a better electrical system, and a redesigned guidance unit. On paper, it was the best version yet. It lifted off successfully, passed the first 40 seconds, but then one engine lost power. The control system misread the drop and started shutting down surrounding engines.

The rocket became unstable, started to roll, and once again had to be blown up mid-air. This time, it was heartbreaking. The engineers had fixed so much, yet the core problems of engine coordination and flight control still weren’t fully solved.

This was the final nail. The Soviet leadership quietly ended the N1 program in 1974. No cosmonauts would walk on the Moon. The Soviets never officially admitted it even existed until the 1990s.

What Happened to the Engines?

Although the rocket failed, the NK-15 and its improved cousin NK-33 were remarkable. They had an incredibly high thrust-to-weight ratio and efficient performance. But there was no Soviet rocket that could use them—so they were shelved, stored in a warehouse for decades.

Then, in the 1990s, American engineers visited Russia and were stunned by the NK-33's performance. Aerojet bought dozens, rebranded them as AJ26, and used them in the first stage of the Antares rocket by Orbital Sciences. So even though the N1 never flew properly, its engine tech helped power satellites into space from the U.S.—a bizarre twist in Cold War history.

Final Thoughts

The N1 was bold, powerful, and full of potential. But it came from a system that lacked flexibility, resources, and time. Without Korolev, the program lost its glue. Without proper testing and iteration, each launch became a gamble. And when the stakes were that high, you couldn’t afford to lose four times in a row.

So yes—Russia did try to build a Moon rocket. And they came close. But in the end, the N1 stood as a symbol of ambition that outpaced its reality. It never reached orbit, but its story still teaches us about leadership, engineering, and how even the biggest rockets can fall without the right support.